Selected poems and writings on process

Declarations

We talk of birds

how pigeons know their way

from place to place like arrows to the heart

We talk of birds

how pigeons know their way

from place to place like arrows to the heart

how we must file our declarations

o so carefully should some hand mistake

the weightlessness of love for goods

and place upon the heart a border

The hand knows what the eye sees

Sitting in firelight, listening eyes closed to Ólafur Arnalds’ Momentary - choir version, I wondered what it might be like to draw, eyes closed, the things that I ‘see’ in my head. Might I draw more fluidly that way?

During my residency at Plas Brondanw, I went out one day without my reading glasses and found that drawing without them freed up my drawing. I learnt later that, after a fashion, ‘drawing blind’ is quite the done thing.

I wear +2.00 magnification glasses when I’m reading and drawing, and double them up when engraving. Without my glasses I see anything that is close up through a haze. To realise then that I’d left my glasses behind that day was one of those oh-shit moments. Bugger — and then bugger it… I walked on and drew.

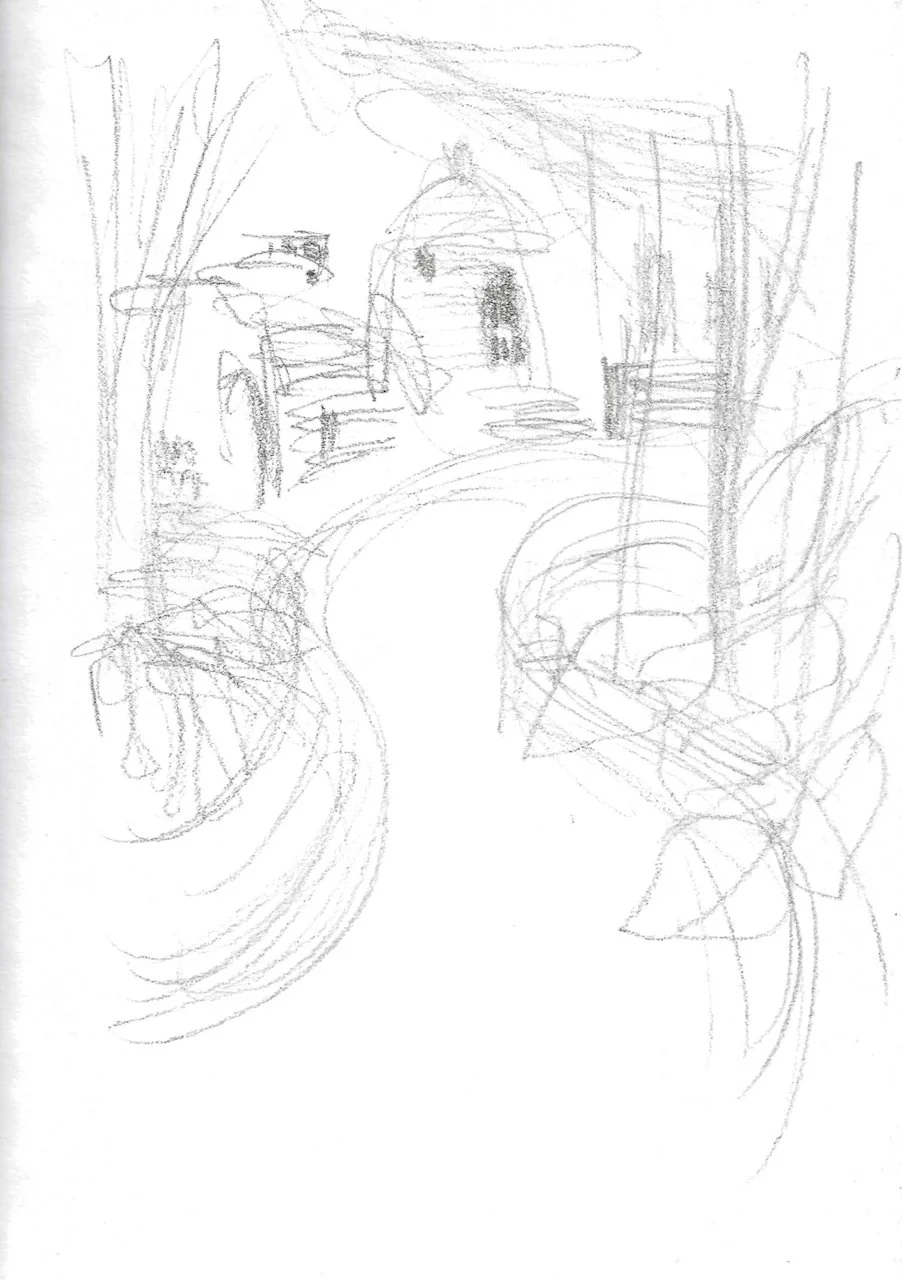

The Lookout, Garreg — a mid twentieth century folly designed by Clough Williams-Ellis.

Graphite in 10.5 x 14.5 cm sketchbook

The Lookout sits on a sweeping bend at the northern end of a run of seven late nineteenth century terrace houses as you approach Garreg from Beddgelert, and as I looked down at my drawing (through my glassless haze) I felt that I had captured something of the feeling of the place — the movement of the road, the perilous location of the houses, the way that the trees crowd over everything. Had I been wearing my glasses, I would have drawn the tower more ‘realistically’ (a phrase that comes with innumerable caveats), but most likely lacking in vitality. I spent the afternoon making drawings like this and since then, when I am outside I draw either exclusively without my glasses, or without them in the beginning. My eyes see, and my hand feels what my eyes see, and keeping my eyes on what I am looking at I see it better and draw better.

A couple of weeks ago, I took this approach a step further. Sitting in firelight, listening eyes closed to Ólafur Arnalds’ Momentary - choir version, I wondered what it might be like to draw, eyes closed, the things that I ‘see’ in my head. Might I draw more fluidly that way? I took two A3 sheets of cartridge paper and taped them to a board, put Momentary on loop, and stood at the easel with my right hand at the top so that I could orientate myself to the paper, a small stick of charcoal in my left. Eyes closed, I listened, conjuring moments into my head. And then I drew.

Two figures

Blind charcoal drawing, 42 x 60 cm, cartridge paper

I felt more than saw. Something vague — the bubble of an image in my head. Something that I couldn’t really nail down. There was the music. And the music made my hand move, pulling the flat side of the charcoal onto the paper to call up first the sun, then waves in the sea, an island, light sweeping over one, two figures sat on the beach watching the sun go down. With the charcoal, my arm outstretched, my eyes closed, I was literally touching what I was trying to draw. When I opened my eyes at the end, I was pleasantly surprised by what I had drawn.

Inspired, I googled ‘drawing eyes closed’ and read up on ideas related to what I’d done.

Artists will, I imagine, have always had a go at drawing ‘blind’. I mean, why not? Kimon Nikolaides, however, is credited with developing ‘blind’ drawing as a practice. In his book The Natural Way to Draw, he details a specific exercise for training people in how to see what they are drawing, arguing that ‘Learning to draw is really a matter of learning to see’. And his idea of seeing involves not only seeing through the eyes, but through all five senses and in particular through the sense of touch.

‘Contour drawing’, as he describes it, involves focusing on the contour of what you are drawing (as distinct from the outline) and imagining that your pencil is physically touching that contour. When you are convinced that it is actually touching the contour, you follow it with your ‘touch’, feeling more than seeing and you draw. Critically, you don’t look at your drawing unless the contour leaves the edge of what you are drawing and turns inward. If it does, you place your pencil on a new starting point and follow the contour again — regardless of whether this contour is on the edge of the subject or inside it. Drawing like this should, he states, be done ‘slowly, searchingly, sensitively.’

Betty Edwards drew on Nikolaides’ exercise in her book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. She calls her version ‘pure contour drawing’ and it differs from Nikolaides in that looking at the drawing is prohibited throughout the entire act of drawing.

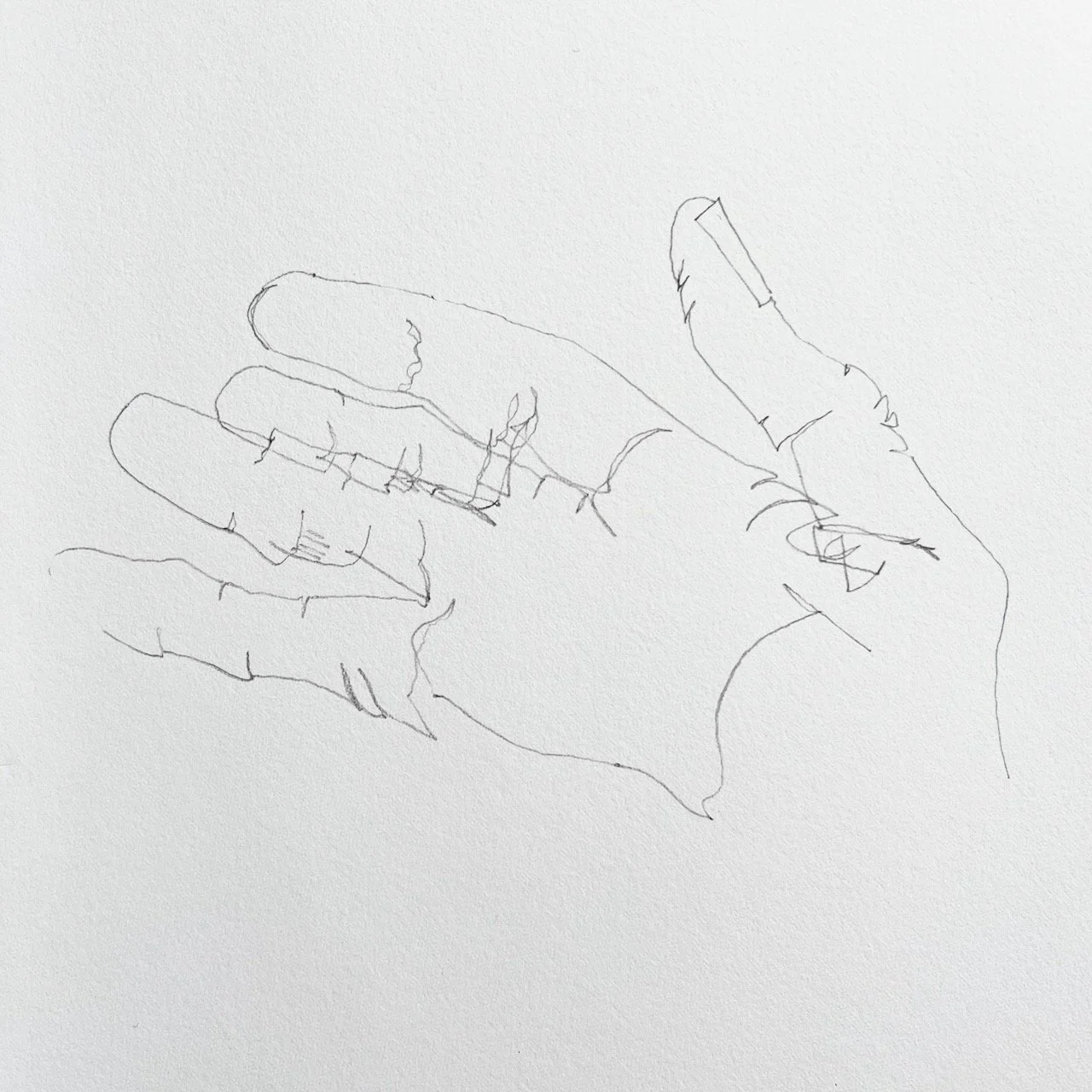

In Edwards’ exercise, you sit side on to the subject of your drawing. She suggests using your hand as your first subject. You look at the hand that you are drawing, your paper at a right angle to it, out of your sight, and you draw the palm of your hand, following first one crease and then the next and so on for five minutes, and all the time looking solely at your hand and never at your drawing. The idea here is not to produce a ‘good’ drawing, but rather to train the brain to see in a different way, shutting out what see calls the L-mode of the brain, and allowing the R-mode full rein — the R-mode being more associated with the ability to draw.

Neither contour drawing nor pure contour drawing were quite what I had done that evening, but they sounded interesting so, I had a go — first at Edwards’ pure content drawing and then Nikolaides’ contour drawing.

I confess that I struggled a bit with the pure contour drawing — not so much because it didn’t produce a ‘good’ drawing (in its way, the marks are interesting), but more because I was unsure when to follow one crease, one line, rather than another. Perhaps I had not fully left the L-mode behind; I was making decisions rather than just looking. In contrast, I found Nikolaides’ exercise rewarding. The hands I drew are demonstrably my hand and yet not my hand. I like the fractured quality of them — the slippage, for example in Contour drawing 1, between hand and wrist, and between one phalange and the next phalange in each finger. This fracturing of the hand seems to capture something of the movement of which a hand is capable. In contrast, the drawings below are ones that I did a couple of years back whilst looking both at my hand and at my drawing. They are ‘better’ drawings, nor ‘worse’ drawings; simply different.

Studies of a hand

15.5 x 20.5 cm, graphite, Fabriano Classic Artist’s Journal

References:

Betty Edwards, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (4th ed.), 2012.

Kimon Nikolaides, The Natural Way To Draw: A Working Plan For Art Study, 1941.

Burnt wood and fingers

I stand in the shade of an oak tree

burnt wood in my hand

conjuring shapes from the past

I stand in the shade of an oak tree

burnt wood in my hand

conjuring shapes from the past

The cairn at Dyffryn Ardudwy. On a hot day in May, circling the dolmens, their apron of stone, I looked for the best view — the sun ushered me into the shade and I drew.

Charcoal, if worked with the fingers, has a magical quality. I generally begin a charcoal drawing by blowing charcoal powder onto the paper and rubbing it in with the tips of my fingers, the palm of my hand. The paper becomes ground - more approachable than white. I then take the long side of a stick of charcoal and work it flat so to speak over the surface of the paper, building up tone. Shapes emerge. If it is a face I am drawing, the shape is a ghost.

I recall a self portrait. Call being an apt verb. From the blended tones a face appears — not mine. Shaggy, lionesque hair, a Turin Jesus. I add more tone, blend it with my palm and the face disappears. I work in its sockets, shape the cheeks, the hair, and a woman appears through the grey cloud. Not me, these conjurings, but something that the fingers feel rather than what the eye sees. I worked on more charcoal — to the eyes, the brow, the chin and a third face appears. Not me either, but close enough.

The magic is that these things come to be. From paper, burnt wood, dust.

And here I am, a hot day in May standing at my easel in the shade of a tree. I’ve marked its bough on the paper, vague shapes for the stones, am lost in the moment of doing. And then a thought calls me and I realise what I’m doing: holding a piece of burnt wood, drawing it down the paper, blending it onto the surface with my finger tips, much as artists in caves once did on walls of stone, and I standing drawing stone.

A holy moment with no god in it

shared with a ghost from the past

What words do

To begin in a roundabout way — John Berger:

“Then, quite soon, the drawing reached its point of crisis. Which is to say that what I had drawn began to interest me as much as what I could still discover…”

To begin in a roundabout way — John Berger:

“Then, quite soon, the drawing reached its point of crisis. Which is to say that what I had drawn began to interest me as much as what I could still discover. There is a stage in every drawing when this happens. And I call it a point of crisis because at that moment the success or failure of the drawing has really been decided. One now begins to draw according to the demands, the needs, of the drawing.”

Berger is here describing looking. The kind of intense looking that occurs when drawing from life (in his case, a life model). It was an intensity that left him feeling as if he inhabited the body that he was drawing. I get this idea: psychologists call it ‘flow’. The self disappears for a moment — the conscious mind banished and we are in the zone. The point of crisis comes when we become aware of what we are doing. At that moment, we cease to feel. We think.

A dangerous moment. And so to words.

What Berger describes in respect to drawing holds true for poetry. There is a moment in writing a poem when we are fully inside the poem. It is an honest moment and curiously wordless — pictorial, almost. And then something jolts us. We step outside and begin to think about what we have written. And the danger when we step outside and become conscious is that we might think as a poet, or leastways as we think a poet thinks. We might do poetry.

A case in point.

I have been updating my website. I wanted to make more of my homepage — to give people more of a reason to delve deeper into my work. Images, definitely, but I also felt the need (don’t ask me why) to say something about my work. And I struggle to say things about my work. I become noble. Pompous. Untrue. The more I write, the more the untruths. Writing is labelling; writing about oneself and what one thinks is to write at best partial truth: to construct one narrative amongst many possible narratives. And as any author knows, characters (the I, you, they) have a habit of doing what they want to do.

The one constant is change

That phrase was as much as I could manage. It is how I see the sea, the sky, rock, stone, people, what we make, and what happens to what we leave behind. I think it captures, in part, what my work is about. I slept on it.

Come the morning, this happened:

The one constant is change

for a moment

I track its fleet feet

For a moment is a hinge. It emphasises the momentariness of any supposed constant and the momentariness of change; at the same time it feeds forward to the human action of the poem — the pursuit of change, the running after its fleet foot, the re-telling of it, the painting of it, all of which is itself momentary.

When I read what I had written, and that phrase ‘fleet feet’, I couldn’t help thinking of Aesacus and his fatal pursuit of the nymph Hesperia. Almost immediately, I changed ‘track’ to ‘pin’. Pin: to hold down — much as a lepidopterist might do to a moth. To fix something in position. To make it permanent. Is this what I aim at in my art I wonder? or is this in the end what words do?

Reference: John Berger, ‘The basis of all painting and sculpture is drawing’, in Permanent Red, Verso.

A first etching

I’ve been itching to try my hand at etching for quite some time and last week had an opportunity to do so with fellow artists Andy Abrams, Jane Evans, Aimee Jones, and Ann Lewis.

I’ve been itching to try my hand at etching for quite some time and last week had an opportunity to do so with fellow artists Andy Abrams, Jane Evans, Aimee Jones, and Ann Lewis (1). For a year or so, we have been meeting up in Conwy on a monthly basis to chat about printmaking over a pint, and latterly, we have begun a practical exchange of practice. On the first occasion we each made an intaglio print using tetra pack as a base plate, and last week we had a go at etching. We were led in this by Aimee and took advantage of Andy’s wonderful studio in the Conwy Valley. As etching was either completely new to or long-forgotten by all but Aimee, we started with basics — degreasing the plate (on the day, aluminium).

Etching is similar in some respects to drypoint in that both techniques involve making marks into the surface of a plate and it is these marks below the surface of the plate and not on the surface of the plate that prints. In this way, both techniques differ from relief printmaking processes such as linocut and wood engraving. They differ also from themselves in that in drypoint the tool (most frequently an etching needle) physically scores the surface of a plate to create a mark, whereas in etching the marks are etched into (‘bitten’ into) the plate by a chemical reaction (i.e. when the plate is dipped into copper sulphate solution or some such mordant). To protect the plate from being bitten into uniformly, the plate is covered with a ‘ground’. Etching needles (or anything else that can work through the ground) are then used to draw through it to the surface of the plate. Where the metal is exposed through this drawing, it is bitten into by the copper sulphate solution and a mark forms in the plate; where it is still covered, the solution has no effect and leaves no mark. It is important therefore to ensure that the solution cannot get under the ground, hence step one. Degrease the plate. This Aimee did by rubbing them with a mixture of whiting (ground chalk) and soy sauce. She then rinsed off the degreasing compound under a tap (checking that it ran clean off the plate), dried the plates with newsprint and applied the ground — B.I.G.

Degreasing the plate with whiting and soy sauce.

B.I.G. was developed Andrew Baldwin as a non-toxic alternative to traditional ground. It can be worked soft (i.e. wet) and then hardened off before it is dipped into the chemical solution, or worked hard from the outset. We did the latter, rolling a thin layer of ground onto the plate, and then baking it for 6 minutes in an oven set to 135C. B.I.G. comes as either a black or a red compound and I was glad that the one that Aimee had brought with her was red as this made it easier to see the pencil marks that we would later trace onto the hardened surface.

Oven ready. Plates prepped with B.I.G and ready to bake

For this, my first attempt at etching, I chose to work on a detail of face which I had drawn some time back and which I hoped would provide a good opportunity to explore line work — something that I have found myself to be doing more and more of in my linocuts. I traced the detail and then transferred it to the ground and began ‘drawing’ through the ground to the surface of the plate with an etching needle. This was a joy: I’ve worked with drypoint in the past and found scoring into the metal to be hard work on the fingers and hand and, in comparison, the ground was relatively easy to work. Tilling, rather than digging. All in all, it took something in the order of 90 to 120 minutes to prepare my face for its bath.

To etch our work, we dipped our plates into copper sulphate solution and left them there for about 15 mins — agitating the surface from time to time with a feather to remove bubbles. Andrew Baldwin recommends a solution made to a density of 38 baumé. Not knowing what this means, I asked Aimee how ours was made up and also looked online for a few recipes. The folk at Handprinted suggest making up a solution in a plastic container with 1 litre of warm water into which is dissolved 100g of cooking salt prior to adding 100g of copper sulphate crystals (this is the mix that we used). Jenny Gunning (at Ironbridge Fine Arts) suggests a weaker solution for aluminum (and also for zinc): 12.5g salt and 50g copper sulphate to a litre of water. For steel (and again also zinc) she advises a stronger solution made of 200g salt and 200g copper sulphate to 1 litre of water. Both Jenny Gunning and Handprinted recommend wearing a mask and gloves when making up and handling the solution, and they both warn against pouring the solution down the sink as it is harmful to aquatic life. The solution can be reused and can be disposed of by letting it evaporate over time into a powder which can then safely be binned.

Etching the plates in copper sulphate solution

When the 15 mins was up, and the solution had done its work of eating into the exposed parts of the plate, we removed the plates and cleaned the remaining ground from them with a sponge and a non-toxic paint and varnish remover (Andrew Baldwin suggests Home Strip). It was at this point that we got to see for the first time the marks that we had etched into the plate. A lovely moment.

My etched plate

We then dried our plates and inked up — not, as I’m used to doing, with a roller, but with mount board and scrim. First, we smeared ink over the surface of the whole plate with mountboard, and then slowly worked the plate all over in small circular motions with scrunched up scrim to force the ink down into the incised marks and to wipe it clear of the surface. This finger-aching work took me a good while to do. Some of us also used cotton buds to further clean the plate and to add highlights. I chose not to do this as my experience of inking intaglio plates in the past had resulted in me cleaning the surface so much that I took ink from the marks and was left with faint prints. I didn’t want another faint print.

One by one, we then pressed our prints on Andy’s etching press, using paper we had previously soaked for twenty minutes and then dried to a damp matt state between sheets of blotting paper. I was a little disappointed with my print when it came off the press. I liked the line work, but once again it struck me as faint — particularly when compared with everyone else’s work. What, I wondered was I doing wrong? Lines not deep enough? Same old problem of wiping out the ink?

The proof. Faint

That said, I was very pleased to have had an insight into the process and pleased to see my work alongside everyone else’s when we made a one-off group print. I headed home after an enjoyable day with a keen desire to try pulling more prints from my plate.

A print combining everyone’s work. Left-right, top-bottom: Andy, me, Aimee, Jane, Ann

Which I did — albeit with a different ink and with my spoon and not a press.

We had used Hawthorn Stay Open ink in the studio — an ink that I have used a good deal in the past and with good results for both linocuts and wood engravings. I wondered though if it was the ink, rather than my too zealous wiping of the plate that had left me with a pale print, so back at home I tried an ink expressly made for etching: Cranfield’s traditional etching ink. The tone I used is called ‘Bone black’; fitting, given the anguish in my face.

Owing to the amount of pressure that is required to force the receiving paper into the incisions of an etched plate and therein to transfer ink to paper, it is generally held that an etching press is a pre-requisite for etching and for intaglio in general. One of the essentials, as Lumsden puts it — noting that it is the lack of a press that ‘prevents many at trying their hands at engraving plates’. Such a lack had indeed held me back from doing so, and being again reduced to my spoon (albeit with a new ink), I was fully prepared to be disappointed with the quality of any print that I might achieve with spoon alone.

I was pleasantly surprised by the result (see below). Notwithstanding that the print is small (10 x 10 cm), and notwithstanding that it was heavy work on the hand to print, the print has a good quality of line and this I put down to the ink. It would be hard, I’m sure, to work a larger piece with a spoon alone, but having achieved what I feel is a good result has given me the spur to do more etchings. I have bought some zinc plates, some B.I.G., and am ready to go.

For the care of the land

10 x 10 cm aluminium plate etching, pressed with a silver spoon and printed with Cranfield Bone Black Traditional Etching Ink on 250 gsm Somerset Satin paper.

Postscript

I showed my etching to four people the other day. None of them particularly liked it. ‘You do like those swirly lines, don’t you.’

I put the etching in a cheap frame and two days later showed it to them again. They all liked it. ‘O my god — I’d buy that.’, said one.

I wonder what this says about how we perceive art.

Footnote

Jane, Aimee, Ann, Andy, and I are a relaxed bunch — disparate in technique and subject matter, but connected in part by location and in part by a love of printmaking. Ann works predominantly in reduction linocut and is well-know both for her landscapes and her work as past President of the Royal Cambrian Academy. Jane is known for her gyotaku prints of fish and other creatures of the deep and has recently begun working with lino. Aimee works with intaglio processes and dry media and is particularly drawn to corvids. Andy draws inspiration from the Carneddau and works with grey tone in photogravure and linocut.

Andy Abram: https://andyabram.co.uk

Jane Evans: https://gyotakugifts.co.uk

Aimee Jones: https://www.aimeejonesartist.co.uk

Ann Lewis, RCA: https://www.annlewis.co.uk

The time of villages

I’ve come to think that the less words there are in a poem, the more freedom is left for what is said…

How many words does it take to make a poem? How much space should a poem leave? How much should it constrain in order to liberate the space that it seeks to leave? I’ve come to think that the less words there are in a poem, the more freedom is left for what is said — and by said I mean not by the poet but within our heads, for words are prompts not vessels. We make of words what we will, and it is a poet’s job to offer them and let them go.

The title of this blog is a poem; here, as a chant, it is again:

the time of villages

Five words, one line, unpunctuated, a monoku if you like, yet hardly itself a sentence, let alone, perhaps, a poem. In writing the phrase, I had a specific set of thoughts, moments, images in mind. I could have gone on, but I felt that I had said all that needed to be said. For me, the poem is a lament and as such I believe that its force is political, for a lament describes not only loss but also possibility — it is a crying out for something. Which begs the question, for what?

Villages mean different things to all of us, and to each of us different things at different times and in different moods. Idylls, for example, places of escape; places, conversely, to escape from. And time? ‘the time’? Was there, is there, a time of villages? What is, what was, what could that be like? And there now, and in the paragraph above, I have begun to do what I shouldn’t do — to explain — and it is o-so tempting to go further and say (now and always impossibly) what for me in the moment of its writing the poem meant, but then I would undo it as poem and make of it an essay:

the time of villages

Abandonments

I am drawn to abandonments — to places that once were inhabited and which now stand empty and in ruins. And I have my own abandonments too: things that I have given up and which the present buries such that not a timber, nor stone remains.

On the surface.

I am drawn to abandonments — to places that once were inhabited and which now stand empty and in ruins. And I have my own abandonments too: things that I have given up and which the present buries such that not a timber, nor stone remains.

On the surface.

Today, I was trawling through photos on my laptop, looking for a photo that I had taken a few years back when thinking about the composition for a print that I am yet (perhaps never) to start, and en route through this archaeology of myself I stumbled upon a stone. Well — a linocut of a stone. Carved into the stone, a monoku, a one-line poem that I had written many years before and which had previously formed the basis of my first attempt at lettering in a relief print. I remember the process of working the letters with a gouge, and remember too my feeling of disappointment upon pulling a proof from the block and seeing the print for the first time. I decided then not to edition it.

Having dug it up today, some two years after making it, I am struggling to put my finger upon what it was that I disliked and all that I can come up with is the fact that it’s not perfect. By which I mean that it falls short of my vision.

Someone, somewhere, will, I am sure, have said that perfection is the enemy of art, perhaps the root of all evil. And it is true that finding fault with things can hold progress back, and true too that there is no such thing as perfect. There is only, ever, right in the moment, and right now — thinking as I have been over the past few weeks about working words into a print — this print for me has found its moment. The sentiment is as pertinent now in these days of loud and mouthy leaders as it was then and ever has been, and having let the print lie buried for two years I can see it now for what it is: a print, an object, a thing, rather than something that with my hands, my head, my eye, I made.

N.B. Just prior to uploading this post, I checked through its settings and noticed that its given url ended ‘anbandonments1’ — the ‘1’ suggesting that I had previously written another post called ‘Abandonments’. I checked back and, five days to the year one year ago I had in fact started a post called ‘Abandonments’. I got no further with that post than one sentence, and then abandoned it. That I come back to the same theme today, one year on, and that I find this print today when I am again thinking about prints with words, is something that I take less as coincidence, or fate, or as something divine, than as the strange workings of a subconscious mind which alone knows what it has buried.

Rhydymain Poems

Some twenty years back, having left a steady job in Aberystwyth to do a PhD (which I in turn I left) I got work in Liverpool. At the time I was living in Taliesin, Ceredigion, on the West Wales coast…

Some twenty years back, having left a steady job in Aberystwyth to do a PhD (which I in turn left) I got work in Liverpool. At the time I was living in Taliesin, Ceredigion, on the West Wales coast, and for a while I used to travel up to Liverpool on a Sunday night and then back home again on a Friday evening. The road I took twisted through mountain passes, above silvered lakes, over empty moors until some two hours later, it hit a dual carriageway and thereafter went downhill. Invariably, a little into the journey, poems would start working their way into my head and by the time I got to Rhydymain I’d have to pull over and start scribbling them down before I lost the lines. I wrote a good many poems this way and thought of them, in my pompous moments, as my Rhydymain Poems. My pomposity stopped short of trying to get any of them published as I had then given up thoughts of being a poet and was fully absorbed in teaching at university. From time to time I remember lines from these poems and revisit them, and today I thought to ‘publish’ a couple of them here.

Having accumulated boxes of poems over the years — some of which I hold to be very good, and others to be terrible — I often wonder at all of the art that people make and which rarely, if ever, sees the light of day. Every so often, a Keith Cunningham, a Ron Gittens, an Agnes Martin pops up: an artist who withdraws from the art world but continues to paint for thirty, forty, fifty years and whose work becomes visible only upon their death. More often than not though, what is hidden remains hidden and I imagine that this is particularly so with poetry. There must be so many wonderful poets out there in the world who, for one reason or another, do not want to publish their work (or who are unable to find publication for it), and whose work as a consequence lies buried in files and drawers until their death when, at best, it is held onto by a loved one for sentimental value alone… for a while. And there must be so much good work too, that is binned or burnt by an artist in their lifetime, the lines of which remain only in the artist’s head until they, like the head, become ether. In as much as we know a bit about what lives near the surface of the sea and near nothing of its deeps, it is a shame that oftentimes what we know of people and of their acts is noise, and in that noise so little of the magic of so many people is seen.

And so, two Rhydymain poems — neither of which are great poems, but both of which may, I hope, offer points of recognition, and generate perhaps a thought, a smile somewhere.

Two

(For Morien)

Da—

dee?

Da-deeeeeeeeee

what you been doing Daddy?

I’ve been teaching, Pudding

I’ve been teaching too

his nappied voice echoes down the line

and I smile across the houses

moors and mountains between us

as he goes off to work at jigsaws

singing songs of sheep

Emigre laments

to coal smoke in the still moist air

your green and sheep-shorn limbs

to skies that slip and bleed on mountains

the coming evening mists

to slow waves and winter seaweed

ache of pebbles on an ebbing tide

my body says goodbye

come now cold steel and glass of cities

your puddled piss and pavements

bring starless nights to scar my sight

and brutalise my sighs

I am yours now for your pennies

undressed eyes open wide

Positive and negative monotype

Over the past few months I have spent a lot of time working on black-line prints. These, by their nature, take considerable patience and care to carve. It was a nice break therefore to spend an afternoon creating some low-stakes monotype prints.

Over the past few months I have spent a lot of time working on black-line prints. These, by their nature, take considerable patience and care to carve. It was a nice break this week therefore to spend an afternoon creating some low-stakes monotype prints.

Monotypes are created by applying ink onto a flat surface such as glass or acetate, then laying paper over the surface and working its underside so as to press the ink from the glass onto the paper. How the ink is laid down, and how the paper is worked determine that nature of the print that is achieved. Ink can, for example, be applied in a painterly way, such that when the paper is pressed the image pulled from the surface is a mirror image of that painted or drawn onto the surface. The Eighteenth Century poet and artist, William Blake, produced some of his work this way. Alternatively, the ink can be laid down flat and without feature, and the image then achieved by lightly laying down paper onto the ink and using tools to ‘press’ the ink selectively from the paper. The tools used might include pencils, brushes, metal instruments, the hand, or anything else that when pressed onto the paper will make it pick up ink. The finer the tool and the lighter the pressure, the finer and lighter the mark and tone.

Monotypes are, given the nature of the process, singular beasts. They are non-repeatable and in this way they share something with painting and drawing —though, unlike both, the process involved in creating a monotype is a blind one in that the image remains unseen until the paper is pulled from the ink. This can be both exhilarating and frustrating in equal measure.

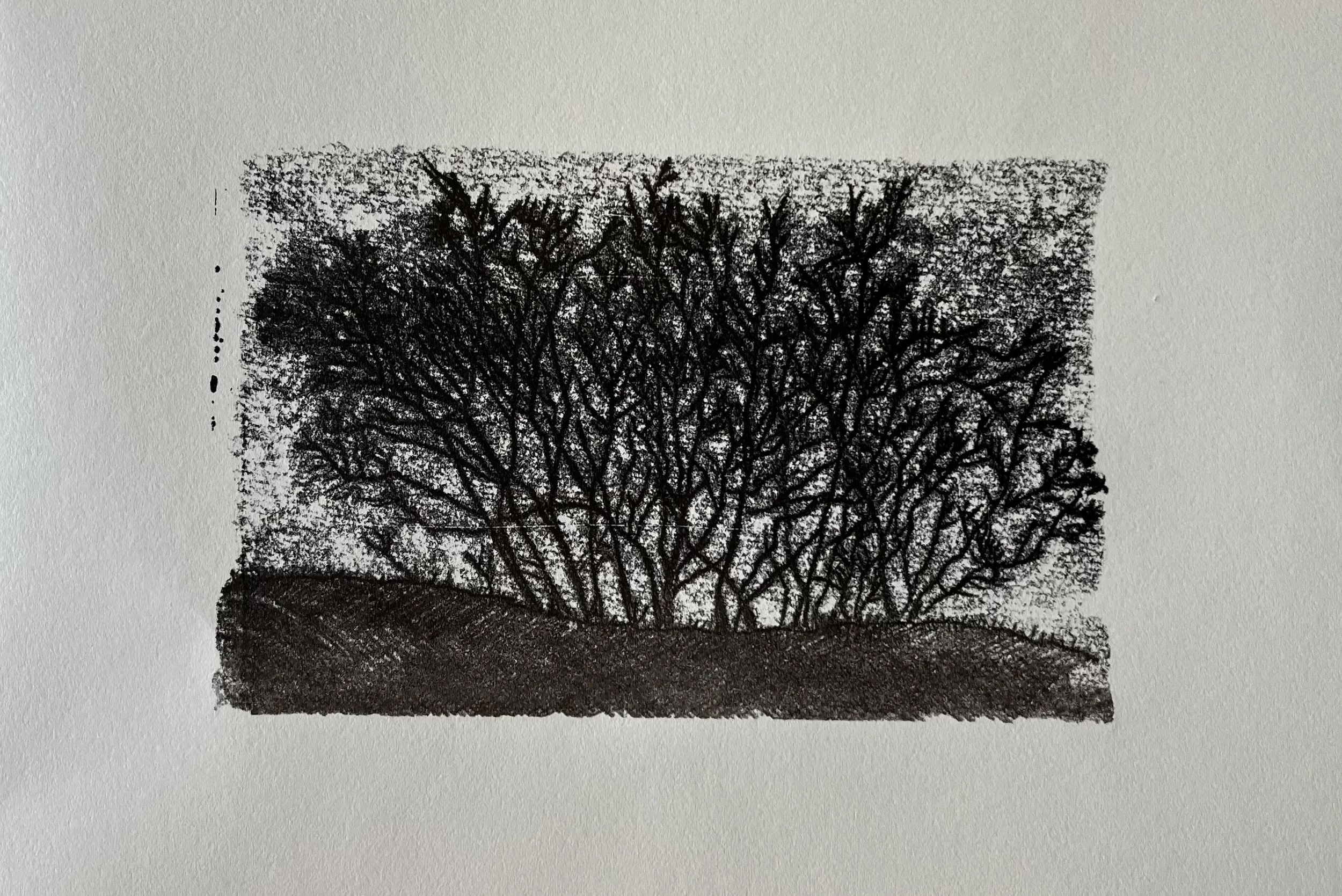

The print below is monotype that I based upon a sketch that I made one evening at dusk. To create it, I marked up guidelines for ink and paper on a glass sheet and very lightly laid down a 15 x 10 cm rectangle of letterpress ink. I then placed a 25 x 20 cm sheet of 145 gsm Zerkall printing paper over the surface (having previously taped a 15 x 10 cm piece of typing paper to its reverse side in the area that would lay over the ink). Taking care not to press onto the paper with my hands, I taped its corners to the glass and then drew onto the underside of the paper with a variety of different pencils. These ranged from 2h to 3b, and the marks that they made can be seen both in the trees themselves and in the cross-hatched lines beneath them. The weight of the paper itself picks up ink and it is this that lends tone to the sky.

Dusk, Monotype on Zerkall printing paper, edition of 1, 15 × 10 cm

It is often held that the surface used to create a monotype can only be used the once. When a monotype is made from drawing or painting in ink, this is certainly true in that any subsequent impressions taken from the surface will grow increasingly paler. After the initial impression is taken, what remains are ‘ghosts’. Such ghosts will be familiar to anyone who has pressed newsprint to a linocut or wood engraving block after printing in order to clean the block. Ghosts are even more evident when a monotype has been created from a toneless area of ink. Once the paper has been removed, ink will have been lifted from the areas that the tools have pressed, leaving a negative impression of the print on the glass or upon whatever surface was used. A print can then be taken from this negative by again laying paper onto the inked area and applying consistent pressure across it. Such a negative can be seen in the picture below.

Night vision, Monotype on Zerkall printing paper, edition of 1, 15 × 10 cm

Sometimes simple is the hardest thing

I recently made a small drawing in my journal of a tree that is comprised of one continuous line made without lifting the pencil from the paper. In part, the drawing was a means of exploring how I might frame ‘The Happy Tree’ that I have been working on through various prints. It was also a study in connectedness.

I recently made a small drawing in my journal of a tree that is comprised of one continuous line made without lifting the pencil from the paper. In part, the drawing was a means of exploring how I might frame ‘The Happy Tree’ that I have been working on through various prints. It was also a study in connectedness. The trunk, roots, canopy of The Happy Tree are all formed from the one continuous line, as too are the trees which grow from and into its roots and the clouds and sun which grow from the canopy of those trees. A bird which sits in the tree is part of the same line, as is a fish which swims through the sky. The drawing measures seven by seven centimetres (roughly two and a half inches across). I was taken with its form and simplicity and decided then to make a linocut from it. Whilst seemingly simple in appearance, the linocut is proving the most challenging I have carved to date.

A continuous line drawing of The Happy Tree.

I scaled the drawing to 16 by 16 centimetres (6 inches across) by taking a photo of it and then printing the photo using an inkjet home printer. I then played around with line to interweave text amongst the roots. It was then that the phrase ‘all things were one thing’ came to me and I decided to lay this line on the surface of the ground as though the peaks and troughs of the script were grass growing from the soil. Happy with the overall effect, I copied the drawing to tracing paper and then reversed it onto a small block of grey lino.

The piece is unusual for me in that rather than interpreting the drawing on the block and changing things as I go, which is my usual practice, I am simply cutting around the line that I have transferred to the block. I use a very fine v-shaped gouge to cut the line (a Pfeil 12/1) and in doing so I am very conscious to avoid cutting into and across the line. It is a challenge not only in respect to carving the script (which being handwritten is full of curves and in some instances is only five millimetres high), but across the whole mass of intersecting lines which constitute the piece. I have spent something in the order of two full days working on the carving to date and still have quite some way to go.

The block after two days of carving.

In general in my work, I work the gouge top down — cutting a mark and then the mark beneath. When it comes to curves, I cut the inside line of the curve first and then the outside. For example, when cutting the ‘o’ in the word ‘one’ in the picture below, I cut the inside of the letter and then the outside. In this way, if I cut too close to the line with the gouge and eat into the line, there is room on the outside for me to widen the line by cutting further away from its edge. The practice works, but gets more challenging the finer the detail, the tighter the curve and the less the room for the gouge to manoeuvre. In this piece, I find it the more challenging still in that it is a mass of conjoined lines and thus what appears as the inside of one line is also the outside of another. There is little room for error and no remedy when a line is cut through other than to remove that line. It is, therefore, achingly slow work.

A flipped detail of some of the script cut into the block. The writing is reversed on the block and therefore cut backwards.

Tabula Rasa

I am currently working on a print in my series ‘The Happy Tree’, and have been sketching ideas for the concept ‘Before happy’. The pencil drawing above is one of the many sketches that I have made so far and one that I particularly like. I had planned to develop the drawing further…

I am currently working on a print in my series ‘The Happy Tree’, and have been sketching ideas for the concept ‘Before happy’. The pencil drawing above is one of the many sketches that I have made so far and one that I particularly like. I had planned to develop the drawing further, but a point came when the eye said ‘stop’ and I stopped. The eye, more often than not, knows when to stop and as a drawing, to me this feels complete.

Having stopped here, and not where I had intended, the question becomes ‘what now?’ Is this sketch my ‘print’? Should it remain a pencil sketch? Should I work it again in lino, in wood, as a drypoint? All these things? Moreover, having realised an idea, do I now have the heart to repeat what (albeit in another medium) I have already done?

The advantage to relief printmaking over the brush or pencil is one of replication. The engraved or cut surface can be used to produce as many prints as the block allows before the block itself becomes worn. In this way, the work becomes more affordable — both to produce and to buy. The downside is that engraving (when it is as an act of translation — the rendering of an image made in one medium into another) can all to easily be experienced by the artist as a chore: not so much a creative act, but the manufaturing of its product.

In general, the process of creating a relief print starts with a drawing. The drawing is then transferred to the block and the block is cut or engraved such that mutliple impressions can be pressed from it. Some artists produce very detailed tonal or line drawings and transfer these onto the block, following which the act of engraving is less a creative act than the pursuit of technique in the attempt to ‘reproduce’ the drawing. Other artists, in contrast, work from loose sketches which they then develop on the block. I count myself amongst the latter, partly in that I believe that the act of cutting reveals things that the pencil cannot, and partly also in that I have a dread of mechanical process. At the moment, this dread is stilling my hand.

One way around the dread would be to sketch directly onto the block and therein remove the need to transfer any previously worked image. Such a process would make the work on the block feel more immediate and less resolved. Another approach would be to cut or engrave without the aid of any drawing at all — in effect, to use the gouge as a brush or pencil. I am drawn to both of these approaches and, but for the cost of discarding expensive blocks, excited by the latter: tabula rasa — not so much the philosophical concept, but quite literally the blank slate.

I’m off to find some.

Melancholy Happy

What is

is because

and includes its was not.

By which, in the case of art, I mean that what we see in a ‘finished’ piece is a product of choices — erasure being one, rejection another. An idea forms, is played with, is subject to the limits of an artist’s technique, is rarely (never) fully realised.

Process is endlessly fascinating.

What is

is because

and includes its was not.

By which, in the case of art, I mean that what we see in a ‘finished’ piece is a product of choices — erasure being one, rejection another. An idea forms, is played with, is subject to the limits of an artist’s technique, is rarely (never) fully realised.

And this is good. It pushes us on.

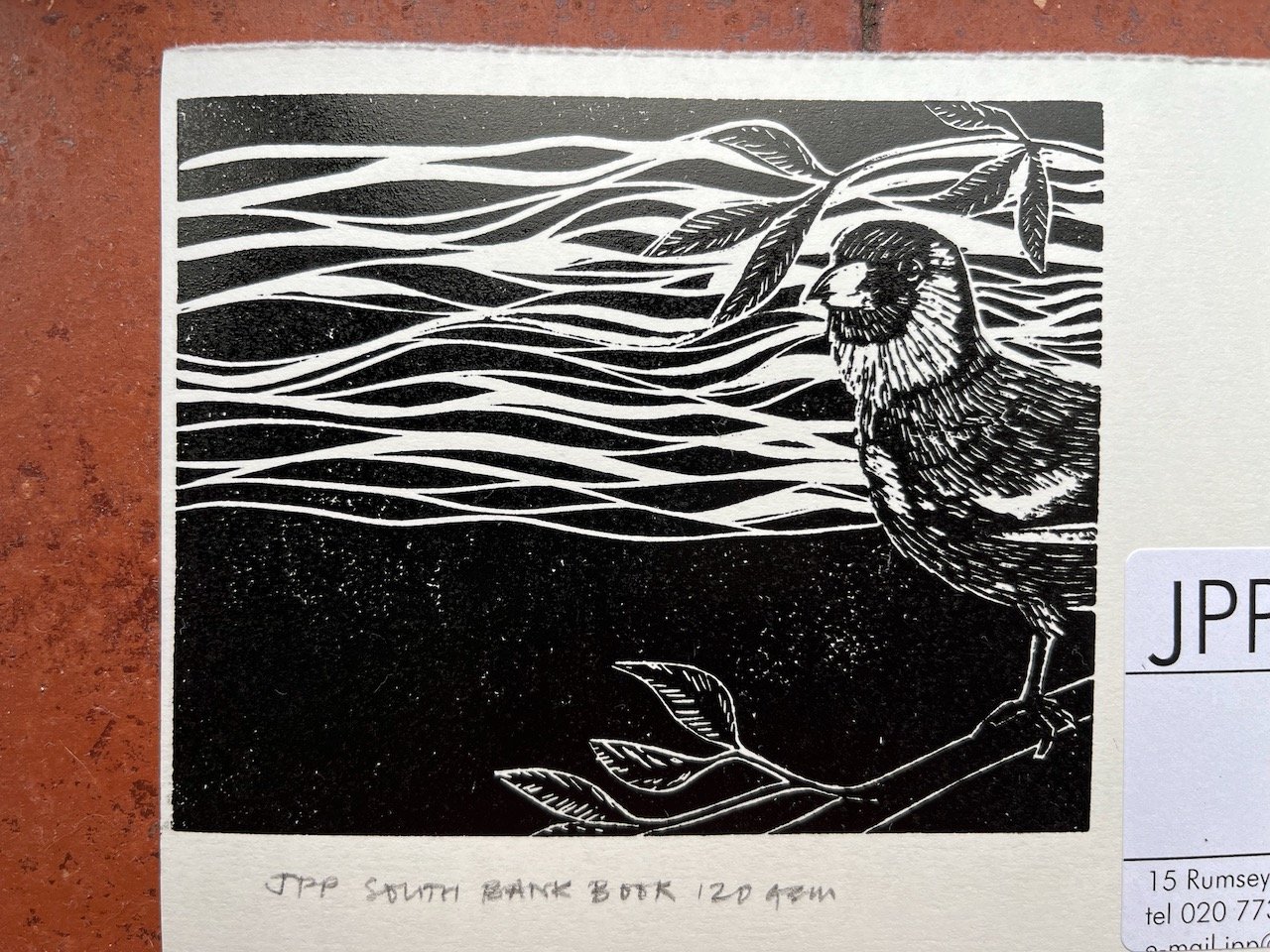

Melancholy Happy. 22.5 x 15 cm linocut on Somerset Satin paper.

Melancholy Happy, my latest print, is nothing if not process, and the print itself but an artefact of that process. In archaeological terms we might think of it as an Iron Age roundhouse or a bone — it is that which remains of the process that formed it, of what was before. And in remaining, its possibilities continue to be, for each time we see the same work of art, we see it differently. Moreover, as long as the artist who created it lives (or indeed anyone lives), the roundhouse has the potential to be rebuilt, lived in, and the bone, so to speak, continues to grow.

The print itself is the second in a series that I continue to work on and which draws upon a conversation with Amandine Robaey and which is called The Happy Tree. Happiness roots in varied streams, and melancholia, on the face of it, would not seem to be one. To be sadly happy, happily sad, happy in sadness — it’s all rather counterintuitive. Yet the music that I listen to when I work makes me happy and that music might best be described as melancholy. Think Arvo Pärt, for example, or the work of Hania Rani and Dobrawa Czocher, and much of the ECM Record catalogue. For me, melancholy happiness is a thing akin to freedom.

In wondering how I might represent melancholy happiness visually, the image that came to me was of a fish swimming through the branches of a tree (see the gallery below). The fish should not be there, but it is there, and it finds itself strangely at home in the waves that branches and leaves make of the wind. Wind and sea are, in the end, sisters: both current. I played with the idea of the fish, made a preliminary sketch for a 15 x 15 cm linocut (with three fish and not just the one), and then decided to work with some lino to see how I might realise the fish. Just the one fish. A quick thing. And then the lino took over. As it usually does.

Moving from pencil and paper to gouge and lino changes the eye, and what started as an attempt simply to cut one fish grew into a journey through its surroundings. This first study gave me then a sense of what I might do, but it didn’t yet capture the concept. Then a bird flew into the picture. I’m not sure why. Perhaps because of the tree, perhaps because in the study there are fish in the sky so why not a finch in the sea; perhaps because I wanted to test my technique — to engrave something I hadn’t tried to engrave before. And so I made a few quick sketches of a goldfinch and then, wondering how I would fashion its feathers and how much detail would come out in print, I made another study in linocut. And yes, the lino took over again.

There is something in the movement of the gouge which of itself creates. Call it rhythm. In the second study I had, like the first, intended to make the sky all sea, but as I got part-way through the piece, the rhythm said stop. It had seen the possibility of negative space (black beneath the sea, the sea become a stream). It is because of happenings like this - the arrival of new ideas - that I consider myself unable to produce multicoloured prints. I like to see what emerges through the act of cutting, and colour in linocut requires clear planning on paper; the work is done before the act of cutting, and the cutting itself becomes an act of translation. My plans are more like whispers. The quiet lets in rhythm.

And so, where once there was a 15 x 15 cm skeleton of a linocut waiting to be cut, there then were two studies and no finished print. Some might call this procrastination. I call it process. The working out of things. And working things out I am left holding two pieces of a jigsaw: a finch in a tree, and two fish in a tree. The question then, should they be joined together? If so, how?

I sketched out a few compositions and then decided on a shortcut: I took a photo of one of the fish that I had engraved then scaled it and printed it multiple times so that I had lots of fish to play with. Ditto with the finch, which I scaled larger than the fish as I knew that I wanted it to sit in the foreground. I cut card for the bough of the tree and its main branches and then arranged the fish into countless compositions alongside the finch. One fish, two fish, a shoal; fish falling from the sky, fish swimming left, swimming right, fish sucked down a dizzying whirlpool. When finally I had settled upon one of the compositions, I copied it onto the lino — my intention being then to shape the sky into sea as in my first study. And then the lino took over. Again.

The penultimate photo in the gallery shows the lino block from which I pressed Melancholy Happy. I cut the finch first, then the fish, the branches and leaves, and then started upon the sea. I worked the sea from the bottom up. Had I worked it from the top down as in the study of the finch, the print would have turned out very differently. Such is chance.

You’ll see that other than the outline of the fish, the bird and the tree, little is marked out on the lino. There are no markings to dictate how I will carve the sea as I know that it will flow organically from the gouge. And it did so. As the sea rose towards the breast of the finch, I felt it tighten and curl. I went with it as I sensed what it was doing — arcing up to meet the branch that hangs over the head of the finch, much as Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa rises from the belly of the sea and as so too rises the wave in my linocut Where the wave breaks. I used pencil to tease out where the curve rose, and felt in a sweep for its arc, and for where it broke. It broke in a shower of leaves above the finch. The leaves which spill into the print from the left join with a branch from the right to form an intentional curve above which I knew the print would be black (as is the case in Two Happies, the other print in the series). I wasn’t aware though that a great wave was hiding in the darkness; the rhythm of the gouge worked out that it was and so I stopped cutting sea and instead did what I rarely do and cleared a large area of lino in order that it would print white.

The fish remain in the air and I think the print works. The white makes things clearer, and though the sea may now appear as a river, it remains sea to me. That said, I ached a little when I first sensed the potential of the wave, for had I seen it when I framed the composition I would perhaps have included more of it in the print. But then the ache knows that waves build from the rhythm of sea and it is for me to find them in the lino.

End of story.

Or so I thought.

After I had editioned Melancholy Happy, I looked back through my journal to start thinking about the next print in the series and I chanced upon the little sketch that I had made when first imagining Melancholy Happy. And so I was driven to make another study — just to see how that sketch might itself have appeared as a print. And, yes, as you can see from the final photo in the gallery, the sea once again did its own thing and became stream.

After the cut the paper

Handbooks on relief printmaking tend to be roughly divisible into two parts: the first and larger part being concerned with ‘the art’ of things (composition, tools, techniques, subjects, examples), and the latter part focusing upon mechanics — that is, printing. Paper, despite the fact that books are made of it, tends to get barely a mention, and yet paper, like ink, can be the making of a print.

Choices. Always choices. The idea, the elements, the composition, the tools, the doing, the stopping — and the paper.

Handbooks on relief printmaking tend to be roughly divisible into two parts: the first and larger part being concerned with ‘the art’ of things (composition, tools, techniques, subjects, examples), and the latter part focusing upon mechanics — that is, printing. Paper, despite the fact that books are made of it, tends to get barely a mention, and yet paper, like ink, can be the making of a print. In the heyday of block printmaking when an artist drew the work, an engraver engraved it, and a printer printed it, the art of all these processes was more recognised than it is today and yet today the jack-of-all-processes artist printmaker has to master all three.

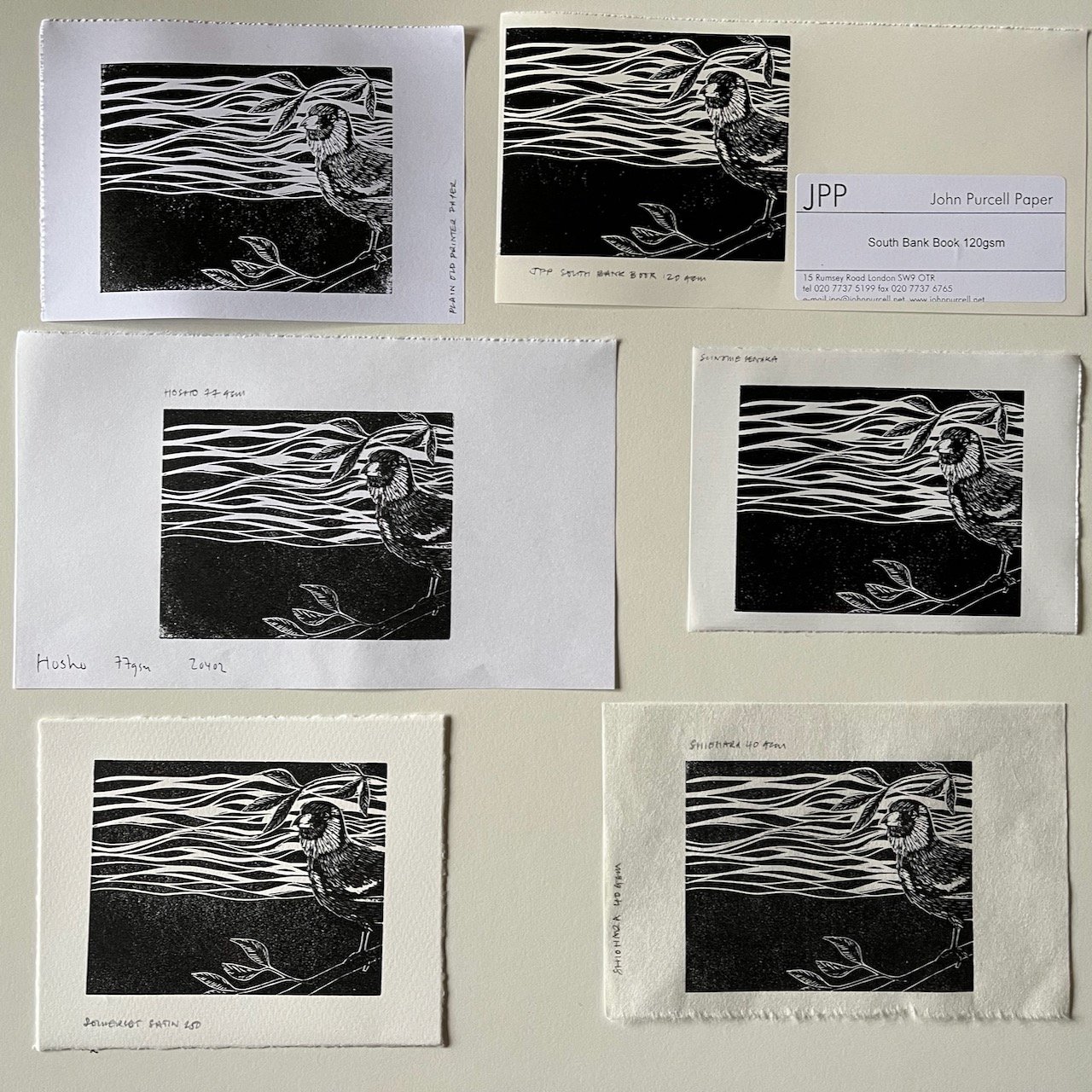

Recently, I have been making studies for a print in my series The Happy Tree. A couple of days ago, I carved a finch into a 10 x 8 cm piece of grey lino. I used a small v-shaped gouge for the finch and I wondered as I worked how much of that fine detail might not make it onto the paper. In comparison to wood block, lino takes a lot of ink, and the more the ink, the more likely it is that the ink will seep into the cuts and the detail be lost. This is where the paper comes in.

If you’re familiar with my work, you’ll know that I have my favourite papers: white Somerset Satin (250 gsm), Awagami Bamboo (110 gsm), and Sunome Senaka (52 gsm). They are all ‘white’ papers, though none are the white of photocopy paper. Sunome Senaka is the brightest of the three papers. It gives a flat, somewhat glossy black, takes detail well and, given that it is lightweight, it is easy to press by hand. Somerset Satin and Awagami Bamboo give a warmer, grainier texture. They are lovely to hold, but take some pressure with a spoon to build the impression. Of the two heavier papers, I prefer the tone and texture of the Somerset and I appreciate the fact that it is relatively local in its production. I wasn’t sure though that it would be the paper for my study, and so I tried out a few.

It’s not warm here at the moment (16.0°c in the studio) and the ink that I used (Hawthorn Stay Open) was fairly thick. It eased up a little when worked it hard with the roller. As I was concerned that the ink would seep into the small cuts, I inked the block relatively lightly for each of the papers that I used and picked up less ink on the roller as I progressed through the papers. My fingers are arthritic, and given the cold, they get quite painful, so I pressed relatively lightly when burnishing with the spoon — this resulted in granular blacks on each of the papers. I used five different papers in all (six if you include the photocopy paper that I used to get things started). In the gallery below the impression appear left-right top-bottom in the order in which I pressed them. They are on: standard photocopy paper (75 gsm), South Bank Book (120 gsm), Hosho Select (77 gsm), Sunome Senaka (52 gsm), Somerset Satin (250 gsm), Shiohara (40 gsm).

The photocopy paper was used for the first impression so as not to waste more expensive paper (the first impression tends to come light and I generally discard it and often the next as well). Even though I didn’t burnish it for long, it picked up more detail than some of the other papers and it rather surprised me. The contrast between black and white though is very stark and as the paper isn’t acid-free and will yellow in time it’s a non-starter when it comes to printing editions. In contrast, the Shiohara (which was the last impression) picked up the same level of detail, but is much warmer and altogether far easier on the eye. To my mind it is, of all the papers, the one which responded best to the subject. It has the gentleness of Somerset and an equally lovely grain to the black, but in being five times lighter it was an absolute joy to press: it required only a light touch with the spoon. The Hosho and (to a lesser extent) the slightly warmer Sunome Senaka lose something through their brightness. The Hosho also lost detail (though this may be due to my having over-inked the block). I was pleased when I pulled the Purcell South Bank Book; its creamy-white surface opened itself to detail without shouting like the photocopy paper, but it is very smooth and there is something of a slipperiness to the black, a lustre that I find a bit unsettling.

The photo below is not very sharp, but it gives you a sense of how tone and texture compare across the papers. I’m not sure which of the papers I’ll use, though I am leaning towards the Shiohara. I’d be interested to know what you’d choose.

Parent Poems

During the early months of the Covid pandemic I spent a good dealt of time with two books: The Poems of Norman MacCaig and Galway Kinnell’s Collected Poems. Both books drove me to write.

During the early months of the Covid pandemic I spent a good dealt of time with two books: The Poems of Norman MacCaig and Galway Kinnell’s Collected Poems. Both books drove me to write.

At first, I suffered MacCaig’s poems. His collected works span from the 1940s through to the early 90s and I read the first thirty or so pages in much the same way as I imagine someone working on a production line might suffer the monotony of their work: I’d bought the book and I felt I had to read it. It wasn’t until I came to poems like Wet Snow (1952) and Climbing Suilven (1954) that I felt I was reading someone whose words might work for me.

Climbing Suilven feels like climbing a mountain. Its rhythm is the treading of the hard up-miles and as ‘parishes dwindle’ as the climber ascends, its world becomes the world ‘between my feet’ — ‘parish[es]’ of ‘stone… tuft’, the next rock, the next step, head down, the leg-burn of it all until the poem reaches its climax and ‘suddenly / my shadow jumps huge miles away from me.’ Nothing speaks of a reaching a peak, of lifting the head and of seeing all that lies beyond and below in the way that that line speaks. The majesty of it all. I copied the poem into a file that I keep for poems that I admire and it has stayed with me. In general though, poems are treacherous things: inconstant as water, any one poem is never the same thing twice.

When I read a poetry collection, I bookmark poems that resonate with me in some way so that I can copy them to my file; when I come back to transcribe them, it’s not unusual for me to wonder why I marked them up in the first place. Such is the momentariness of poems. In as much as poems read and loved when aged twenty will not necessarily be poems loved and read when sixty, so neither will poems read on a grey Tuesday morning in bed be felt the same way when read on a grey Sunday in bed or in sunshine on the bank of the Po. Poems are conversations. Sometimes we are ready to, want to, can, listen to a particular poem and at other times a poem’s words are broken voices in a mist.

Typically, poems that resonate with me make we want to speak back. They trigger something. Many of MacCaig’s poems did this and drove me to write my own poems — not so much in response, but because the thoughts within them sparked thoughts within me. You could call them parent poems. Galway Kinnell’s Collected Poems birthed a few poems for me pretty much from the off.

Before reading Kinnell’s Collected Poems, I’d only previously come across his work through a few poems in anthologies. Those few spoke enough to make me want to read more. His poetry makes me feel that I’d like to have had him as a friend — even if in reality I might not. The Bear was the first of Kinnell’s poems to really stand out for me. It is a poem of twelve stanzas and seven parts. In it, the voice of the poem smells bear. It whittles a stick to two points and hides it in blubber, hoping the bear will eat it. It does, and the voice follows the bear as it bleeds from inside ‘the first, tentative, dark / splash on the earth.’ When the bear dies, the voice finds it, eats and drinks from it, tears it open and climbs in. Now the voice is bear ‘lumbering flatfooted / over the tundra / stabbed twice from within’ and knowing that one day it too will fall. As it wanders, it wonders ‘what, anyway / was that sticky infusion, that rank flavor of blood, that poetry / by which I lived?’ A poem that from the outset is a poem about writing poems, about where they come from, where they go, about how they form from, and themselves form, the writer, about how painful, unwanted, how pointless, how grand they can be to write. To a poet, what is there not to like?

When one has lived a long time alone is another of Kinnell’s poems that has stayed with me. A poem of ten stanzas, each of thirteen lines, and each of which begins and ends with the line ‘When one has lived a long time alone’. Its rhythm is incantatory. It was published in a book of the same title when Kinnell was in his early sixties. I read it when I was not far off mine. The first seven verses of the poem are full of animals: a fly that the one who has lived a long time alone will not swat, but lets go; a mosquito, a toad, a snake — the foul things that one befriends when living ‘among regrets so immense the past occupies / nearly all the room’. By verse five, the long-lived one has found some ease and companions doves, grasshoppers, frogs, a flycatcher, a woodpecker, a pig, porcupine, worm, butterfly — believing that one’s purpose is to know them, having discovered that ‘one likes / any other species better than one’s own, / which has gone amok, making one self-estranged’. The poem is a running from people, from what they do, and from what oneself as a person does, and a running towards the other, to nature, the ‘natural’, to simple. And yet a person cannot be other than a person, this the misanthrope knows and comes to terms with towards the end of the poem having realised that the snake, the bird, the insect, step away to be with their own kind and ‘the hard prayer inside one’s own singing / is to come back, if one can, to one’s own’. It’s a beautiful poem. Sad in many ways, yet full of love, full of hope. In speaking of animals it speaks of other ways of being human. The tragedy is that the trajectory we are on as a species seems each day one step further removed from that which does us and our planet good.

I came back to Kinnell’s poem in early 2022 and as I read it again it drove me to write a poem. In When one has lived a long time, I borrow Kinnell’s first line and make it mine. The poem was published in Ink Sweat & Tears and I would like to thank Helen Ivory, Editor, for seeing something in it.

When one has lived a long time

(after Galway Kinnell)

When one has lived a lone time alone

and not alone your time become

someone’s history and you have grown

tired of yet another war and the world

has it in for you simply for being

wrong nation wrong colour wrong

construct in all its fairy-tale fictions

you begin the long slow weaning from lives

someone makes it their business to spoon

24/7 into your small ever so human head

and dream of an island fish sea-wind

and a life lived companied by no more folk

as can live a long time alone

and not alone on a handful of salty acres

References

You can read Galway Kinnell’s The Bear at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42679/the-bear and you’ll find some of Norman MacCaig’s poems at the Scottish Poetry Library. The books I’ve cited are Collected Poems, Galway Kinnell (edited by Barbara K. Bristol and Jennifer Keller, and published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) and The Poems of Norman MacCaig (edited by Ewen McCaig and published by Polygon).

The Happy Tree

Around eighteen months ago I began work on an idea called ‘The Happy Tree’. The tree grew out of a series of conversations with Amandine Robaey on the nature of happiness. Thinking about the roots from which happiness springs and of some of the manifestations of happiness, we came up with a long and non-exhaustive list of ‘happies’.

Around eighteen months ago I began work on an idea called ‘The Happy Tree’. The tree grew out of a series of conversations with Amandine Robaey on the nature of happiness. Thinking about the roots from which happiness springs and of some of the manifestations of happiness, we came up with a long and non-exhaustive list of ‘happies’. Amongst the twenty-five or so that we listed were ‘wrong happy’ (a form of happiness in which what makes you happy might, in the final analysis, not actually be good for you) ‘forbidden happy’ (a happiness looked down upon for some moral reason or other), and ‘overthinking happy’ (which was both a joke about what we were doing in deconstructing the word ‘happy’, and itself a form of happiness: the pursuit of an intellectual purpose).

Having come up with our list of happies, the aim then was to realise these different happies in the form of a tree. My linocut Two Happies was a first attempt to do so. In Two Happies, a blackbird sits upon a sapling and looks across at a branch which forms around the phrase ‘wrong happy’. The sapling contains the phrase ‘forbidden happy’. The two phrases might be paired in warning. The blackbird itself might be nesting, might be guarding, might be defiant. Two boughs run vertically either side of the sapling and act as a frame. As a result, what was initially conceived of as a tree then became in my mind a forest. I see the forest, but I haven’t yet (perhaps never will) made the print.

In the time between cutting Two Happies and now, the tree took a back-seat and bided its time. This is, I think, what ideas do. There are silent voices in all of us that say ‘hold’. They murmur disquiet. They know what we don’t know. The silence is often called ‘block’ or ‘prevarication’. I think of it as process. The sleep of an idea — its long winter.

A month or so ago, the idea woke up. Since then, I have been sketching a lot and now have in mind the tree as a thing in itself, and also as a series of prints which when displayed together take the form of the tree. The studies below are for two possible prints in the series.

‘Melancholy Happy’ is the happiness derived from that which might on the face of it appear sad. (Happiness is relative: it is dependent not only upon degree and context, but also upon personality). The picture I have in my head for this phrase is of fish swimming in a sky that is sea. The idea marries with a poem that I wrote called Awyr / Sky and in which miles high in the sky ‘sleep swifts like guillemots on waves’. The phrase ‘before happy’ is, like the Dutch concept voorpret, a happiness experienced in anticipation of a happy event. Even if the event itself were never to occur, there is still that feeling of the happiness before. In this sense ‘before happy’ (which contains its other:‘happy before’) is much like an idea.

Bring home the wood

A cold and frosty December morning. Two collared doves spiral twenty feet up from the ground. Almost touching — I like to think they are courting.

I am in the garden, carrying wood (endlessly it seems) down to the wood shed, and the birds’ flight holds me. The air still but for the beat of their wings, the sky blue, the sun breaking low through trees. Little moments.

A cold and frosty December morning. Two collared doves spiral twenty feet up from the ground. Almost touching — I like to think they are courting.

I am in the garden, carrying wood (endlessly it seems) down to the wood shed, and the birds’ flight holds me. The air still but for the beat of their wings, the sky blue, the sun breaking low through trees. Little moments.

Somewhere, a wood pigeon coos, reminding me as ever of childhood, and something within me stills. The impatience to get a job done and move on to the next.

Beautiful are these moments of noticing, when the eye drifts from the task, like now — the Menai silvering its blues — and I stop, have to stop. The wood I am carrying can wait. The job will get done.

During the pandemic, life similarly slowed. I remember now that there was a lot of talk then of work-life balance, and of how, with many working from home, with less people on the roads it became somehow human. The commute, largely, was gone; people spent more time with family, had more time to sit around; we worried less about being seen to get things done. ‘When it is over’, I heard many people say, ‘life needs a reset’. That was what many wanted.

And how fleeting the moment; how quickly capital reclaimed its slaves. Which makes it all the more important now to praise the small things.

I lost my job at the tail end of the pandemic. It was relatively well-paid, but I am thankful that I lost it. I scratch a living now — literally and metaphorically — but I count myself lucky, as now, to be able to stop when two birds take to wing.

Wood

The garden walked me six miles today

stepping up then down its terraced slope

then up and down again

again

ninety times along its twisting spine

to bend and load again

again

a tub of wood to rock

each step upon my thigh and

stack

stack

stack

down by the house as honeycomb

the stove will suck and chew

chortling through the long nights

Published in Response / Response, Dreich, 2021

*The English phrase ‘bring home the bacon’, means to earn enough money to live. In Welsh, the phrase ‘dod yn ol at fy nghoed’ (literally ‘to return to your trees’) translates into English as ‘to come to your senses’. In turn, the English phrase ‘come to your senses’ signifies a return to rationale thinking. Senses themselves (seeing, feeling, hearing etc.) are the means through which we act in and react with the world. In giving this piece the title ‘Bring home the wood’, I draw on all these references.

A Pattern Formed

‘You have spoken of “first patterns” — of images without existence save in the soul of the carver, but which transmutes into matter, making them visible. …And this same “first pattern” — this shape — is, to a hair, what old philosophers called “the idea”.’

‘You have spoken of “first patterns” — of images without existence save in the soul of the carver, but which transmutes into matter, making them visible. So that, long before such a carver’s shapes can be seen, and so obtain their formal reality, they are there already, as forms within his soul. And this same “first pattern” — this shape — is, to a hair, what old philosophers called “the idea”.’

So says the intellectual priest-become-abbot, Narziss, to the lover-vagrant-artist, Goldmund, in Herman Hesse’s Narziss and Goldmund. Goldmund has achieved one great work, a rendering in wood of St. John the Disciple in the likeness of his Childhood friend, Narziss. Another work remains — his Eve, which seeks to capture the ecstasy of love and the agony of death in the face of a woman and which he suffers love, life, and death to see. In the space between the moment of his first pattern and the work’s form fall the years.

I have a head full of first patterns and books full of their first pencilled dawnings and I often wonder about the multitude of visions and half-formed works and words that artists and poets leave behind when they die. Where did they come from? Where do they go? Even if only in the head, these images and thoughts have substance and become the stuff of days; though invisible, they are as real and as substantive as the ground on which we tread. Do they float forever; find a new face somewhere, a new head to fill, or do they, in turn, cease to be in that final gasp for air?

I first read Narziss and Goldmund thirty-some years ago and subsequently forgot the story. I am re-reading it now and nearing the end, and I do not know if Goldmund ever realises his Eve. And if he doesn’t, what matter — for him has she not already been seen? Over and over again? We tend to think of a ‘finished’ work (a poem, a painting, a sculpture) as just that — finished. But to the artist, the poet, I wonder if ever they are, or if rather the work is more in the way of a punctuation — not an end itself but part of the grammar of striving to see. Artists rework their work; poets their words. In this is the search not for one thing, one great work, but for all things… so voracious the heart, so greedy the eye.

The Act of Irretrievables

Carving lino or engraving wood, I find myself endlessly killing what my eyes see. The tool marks a shape; you work around the shape and other shapes appear. Or more correctly, they insert themselves — not having previously been sketched or envisaged — they are born from the movement of the tool. Its water.

Choice is the erasure of possibles.

Carving lino or engraving wood, I find myself endlessly killing what my eyes see. The tool marks a shape; you work around the shape and other shapes appear. Or more correctly, they insert themselves — not having previously been sketched or envisaged — they are born from the movement of the tool. Its water. Many are beautiful. Some are shaped consciously once felt and seen. But most are erased: once seen and never seen again. Fleeting moments. A life in time.

What the eye sees always resides in us. Sediment. A cliff falls; a cloud within us drifts off somewhere and there is what we once saw. Only differently. When I carve letters I begin by cutting the edge of what I have drawn. It is a slow, very concentrated act: eye and hand and tool abandon the world. And then once the letters are marked, the world is recalled: choice calls.

Perhaps it is something I once saw — chisel marks on a monumental stone, lines in a book of lettering — I’m not sure what it is but I find marked out letters beautiful. I rarely start a piece thinking that the marked out letters will remain (they are merely a step towards the bold letter), but when I see them, I invariably want to keep them and then do not. A considered choice, but one which carries with it its grieving.

The piece I am currently working on draws upon a phrase from Genesis: ‘and the evening and the morning were the first [the second / the third / the fourth, etc.] day’. I find it a puzzling phrase: as though night itself were day. In my piece, I have adapted the phrase and run it in a ring around a moon that is sun and a sun that is moon. The phrase reads: ‘and the morning and the evening were the same day’, and because the phrase is carved in a circle, it reads endlessly as though Sisyphus himself were chanting it:

and the morning and the evening were the same day

and the morning and the evening were the same day

and the morning and the evening were the same day

and the morning and the evening were…’

Creation. The feeling I get from letters is the same that I get from shapes. From the sun and the moon rise flames. White on black; black on white. As I carve them, the tool flows into the space between the flames and the eye sees, the hand feels shapes. Many are beautiful and the tools shape, the tools erase and the act is irretrievable.

The House of the Long Stay

Dolbadarn castle lends itself to the artist. Perched on a knoll between the waters of Llyn Padarn and Llyn Peris, and glowered down upon by the Glyderau to the northeast and by the wall that is Yr Wyddfa to the southwest, the castle was painted by Turner in 1798.

Dolbadarn castle lends itself to the artist. Perched on a knoll between the waters of Llyn Padarn and Llyn Peris, and glowered down upon by the Glyderau to the northeast and by the wall that is Yr Wyddfa to the southwest, the castle was painted by Turner in 1798. Hilary Paynter later captured it in one of a series of 14 wood engravings that she made for J. Beverley Smith’s book ‘Princes and Castles’. A romantic spot, but a castle in the end: Owain ap Gruffudd was held there for some 20 years by his brother Llewelyn the Last, and was described then by the poet Hywel Foel ap Griffri, as ‘Gwr ysydd yn nhwr yn hir westi’ (a man in a tower, long a guest). The castle might well be called The House of the Long Stay.

I’ve been over to Llanberis on a few occasions recently in search of a subject. Busy though it is, there are some lovely spots from which to sketch: reed beds at the northern end of Llyn Padarn; rocks that jut out into lake and that are peppered with Scots Pine; the castle itself and the nearby woods. The best spot, perhaps though, is the lake itself. I’ve rowed it when the sea has been too rough to put out, and remember one occasion when, looking as dusk fell at the V of the valley beyond the castle, bruised clouds rolled in and you could watch the very minutes you had before they hit. And they hit in hail. A starkly beautiful moment: the still flat of the water taught as a drum-skin, the hail skipping upon it in elfin delight. I was covered in ice, my hands and face stung, but the magic of the place stuck with me. I hope I’ve captured some of it, albeit in a different way, in a new engraving which for the moment (and borrowing from Caradog Prichard’s novel of the same name) goes under the title of ‘Un nos ola leuad’ (‘one moonlit night’).

In the gallery below are shots of some of the steps involved in making the print. The first photo shows a couple of the quick sketches that I made in the area. The second is of the naked block chosen for the engraving; a small piece of end-grain box wood measuring approximately 6 x 4.5 cm. I darkened the block with a very light coat of Winsor and Newton Black Indian ink; doing so helps me to see more clearly the marks I make whilst engraving. On the darkened block, I sketched the bare bones of a scene using a white Caran D’ache pencil. I ended up sketching it quite a few times, rubbing it out and starting again until I felt happy with the general idea. To engrave the wood, I used three tools. Top to bottom in the photo they are: a medium tint tool (used to cut fine lines); a spitsticker (to dot the surface of the wood and to add highlights); a square scorper (to clear areas that I wanted to print white). To press the image, I inked the block very lightly with an oil-based ink, and then laid a sheet of 250 gsm Somerset Satin paper upon it and burnished the back of the paper with a silver spoon.

The finished print is in terms of its composition pretty much as I’d envisaged it in my skeleton sketch, but the mood is different. At the outset I had imagined a daytime scene with a hot sun and a very white sky, and in the end it turned into night. It is that change of tack that a skeleton sketch allows when compared to a fully developed plan that attracts me to the process. To know in advance quite clearly what you want to achieve and how you will do so makes of engraving a rather mechanical process and something that I would find boring. I approached the block with a vague idea and, as usual, plenty of doubt. I wasn’t sure how I would work the trees, nor how much light to bring in, and it wasn’t until I began the process that slowly, tree by tree, dark by dark, a mood emerged and the block showed me the way.

References:

J. Beverley Smith (2010) ‘Princes and Castles: The legacy of thirteenth century Wales’, Gregynog Press.

Frances Lynch (1995) ‘A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales’, HMSO.

Crawia

Crawia are a form of fence typical to the slate quarrying areas of North-west Wales. Made from waste slate (‘craw’), they stand with their feet buried in the earth, each slate linked to the next with fencing wire that wends its way before and behind them as a weft does to a warp. The very fabric of hills, of fields and villages, they stitch field to moor, house to road, the land to the sea.

Crawia are a form of fence typical to the slate quarrying areas of North-west Wales. Made from waste slate (‘craw’), they stand with their feet buried in the earth, each slate linked to the next with fencing wire that wends its way before and behind them as a weft does to a warp. The very fabric of hills, of fields and villages, they stitch field to moor, house to road, the land to the sea.

I have long been drawn to crawia. Vernacular, they are a product of place and of necessity: a local sense of make-do, when local was how people lived. As peculiar to North-west Wales as knapped-flint houses are to the chalk downs of England, you know where in the world you are when you see crawia. They attract me too in that, like mist breaking in mountains or rising off the sea, they allow a glimpse of what lies beyond. The otherworld.

The road I live on is lined with crawia, and a mile or so west of the village is a short section that separates grazing land from the cockle-strewn shore of the sea. Crouching down, the slates parse what the greedy eye sees.

My ‘Crawia’ wood engraving is based on a series of sketches I made of this section of fence. Doodles at first — what I remembered of the fence — and then sketches made sitting and standing in the grass on a hot summer day and wondering how to compose a piece: landscape or portrait? how high the slate? where the horizon? how high the grass? As always, what remains in the piece is only a fraction of what was seen.